The Blueproject Foundation presents the exhibition “Future Relics” by Elena Lavellés, the third resident artist of 2018, which can be seen at the Sala Project from July 13 to September 30, 2018.

“In this new body of work, Elena Lavellés continues her preview exploration on the three forms of gold (mineral, hydrocarbon and precious metal) to develop a discourse which reveals the interactions between transformation process, local history and the power relations of corporate capitalism.

In this case, the discourse plays with a sort of speculative realism beneath which lies a biopolitic reading which uncovers the connection between the exploitation of the territory and the exploitation of culture.

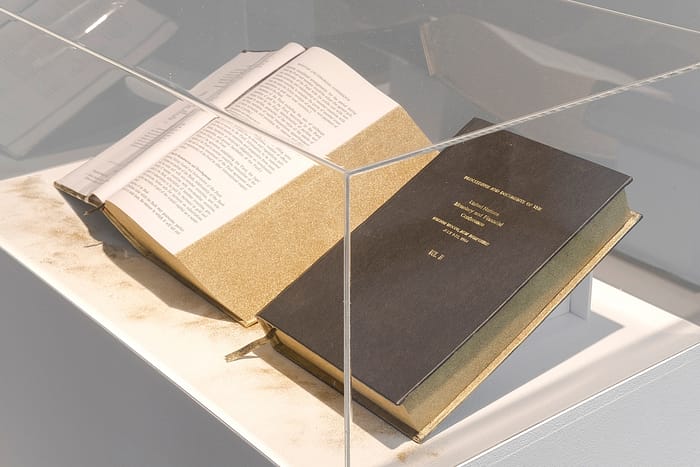

As a starting point, welcoming us at the entrance, we find a work inspired by the Breton Woods treaty, gold-plated by hand. The renowned book is the result of the 1944 agreement, which established the free-trade policies which have governed the world ever since, together with the resulting establishment of the World Bank and the IMF and the consolidation of the dollar as the main international currency.

The other works unfolding after this one are grouped in three sections: a series of relic-sculptures, a set of drawings over topographic maps and a selection of photographs. The artist invites us to re-imagine in between two waters, the land of the imaginary and that of the real. The land of utopia and that of dystopia, an approximation which implies social resistance and the alternatives to contemporary established and dominant processes.

The triad of materials used (gold, oil, and coal) constitutes the foundation of the three installations, which resemble reliquaries, that Lavellés created by reusing discarded waste of the aforementioned materials, suggesting their future disappearance or, at the very least, inaccessibility. If we carry on at the actual rhythm of the so-called Anthropocene, with time any object made up from any of these three materials will become an object of historic interest. The artist also establishes a relation between the religious character of relics and that of capitalism, comparing their viral condition. As Frederic Jameson pointed out: “It is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.”

To emphasize these connotations, Lavellés shows these materials in reliquaries and, furthermore, offers to sell custom-made artworks to be realized with the gold, oil, and coal used in the exhibition, once the exhibition has ended. It is a way to underline the necessity of understanding the dramatic future of a planet of limited resources and the necessity of changing the way we inhabit it.

The drawings are made using topographic maps of the cities and surroundings of Ouro Preto (Brazil), Ciudad del Carmen (Gulf of Mexico) y Gillette (U.S.). The three areas are examples of scenarios which have suffered and suffer the consequences of the mining of the materials in question, what David Harvey has called “the resource curse”.

Maps have always served the purpose of abstracting the materiality of territories and spatial relations. We shouldn’t forget the etymology of the word “Geo-graphy”: earth-writing. Lavellés is truly recovering the original and symbolic meaning of the word. Maps become displays of the dynamics of petrocapitalism and the conversion of resources into the capital flow.

Furthermore, the paper which Lavallés has selected is Khadi Papers, imported from India, which sooner or later will also become a relic, due to its disappearance or its high price once fossil fuels run out. By using this kind of recycled and fair-trade paper, handmade using old medieval techniques, the artist shows the importance she gives to recycling processes and traditional methods of production as tools of resistance against capitalism and its devastating consequences.

Gold, oil, and coal come out gently from small holes which the artist cut in the map, a metaphor of the erosion of the land produced by men through mining.

With the photographic section, Lavellés leaves the symbolism of the other two series and distances herself from the field of allegory. The images show the real impact of mining activities over the real landscape. There is no playing with the viewer, the message is direct and clearly shows the consequences of the exploitation of the land, not only through degradation and extinction but also through contamination and exploitation of human resources. Two of these pictures show what is still called a “natural disaster”, a real paradox since there is nothing “natural” in the mud and chemicals wave which fled from a breach in the dam of this mine. One of the pictures shows the marks left by the wave, while the other focuses on the remains of a house in the Bento Rodriguez village, severely affected by the catastrophe and reduced to a ghost town.

As Rosi Braidotti reminds us: “We cannot forget the tight link between the neoliberal political economy, the variety of exclusion discourses and practices, the marginalization and elimination of entire layers of human population and the devastation of non-human agents and of the planet in its very sustainability”.

The exhibition as a whole shapes a landscape through the three materials which imply multidimensional exploitation – of men and of the territory – and whose impact can be traced from slavery to the present. This way it offers us a reading of the implications of the colonization of nature, throughout which thousands of people were displaced for the use of the territory by multinational corporations for the benefit of the global north.

Thus it becomes clear how every landscape is political and how political ecology and artistic experience are intrinsically connected through the paths which they both offer to understand the interactions between the environment and the economic, social and political.”

Text by Blanca de la Torre (English translation Blueproject Foundation)

On the afternoon of November 5, 2015, the retaining walls of the Fundacão and Santarém dams, both located in the subdistrict of Bento Rodrigues and controlled by the mining company VALE-Samarco Mineração S.A., did not resist the pressure of the waters with waste from the extraction of iron ore, breaking and releasing more than 50 million tons of sludge.

The wave swept through several towns, including Bento Rodrigues, and the toxic waste from the iron ore reached the Doce River, whose watershed is approximately 86,000 km2 and covers 230 municipalities that use its waters for their livelihoods. Scientists and environmentalists believe that it is impossible to recover the river and that the waste will remain in the river for at least 100 years.

Bento Rodrigues was one of the municipalities most affected by the wave of toxic sludge from the Fundacão and Santarém dams. In the incident, 19 people died and the town was practically razed and contaminated by the toxic materials. More than one million people were affected by this “natural disaster”.

People from this and other affected localities have been displaced and relocated to the city of Mariana. In this way, they have not only lost their homes but also their way of life, their community, and their roots.

Three years after the worst natural crime and environmental disaster in Brazil, the mining company continues to go unpunished and to make donations in presidential campaigns to different politicians in the country.

Coal has been one of the most important economies in the United States and was boosted by Donald Trump, in his plan to bring back industries that Obama had shut down as part of his “Clean Power Plan” and threatens global environmental security by withdrawing from the agreements adopted at COP21, the Paris Summit.

In turn, the citizens of the Powder River Basin region have voted for Trump en masse because of his policies to bring back coal mining, a local industry they are proud of and participate in for its impact on the country’s energy production and employment. However, during the Obama administration, they felt criminalized by his policies and censorship of this industry.

Coal problems are not just about CO2 emissions; their consequences are far more profound. Every day, more than 50 trains, each nearly two kilometers long, and each year more than 48 million metric tons of open carloads of coal from the Powder River Basin region travel from Wyoming and Montana through hundreds of small towns to the ports of the Pacific Northwest leaving coal dust laden with arsenic and mercury particles in their wake. This steady stream releases toxic environmental pollutants and a host of health hazards to the communities in its path. The environmental impact is more significant than the construction of the Keystone XL Pipeline would have entailed.

On the other hand, projects to build ports to export these minerals from Wyoming and Montana put at entire risk communities of indigenous tribes living in the Pacific Northwest, such as the Lummi, who are fighting to maintain their treaties with the state so as not to lose their lands and resources to capital and trade.

This eco-park is one of the few protected mangrove areas that have survived in Ciudad del Carmen. Due to “urban encroachment” resulting from the development of the oil industry, a large percentage of these mangroves have been destroyed, putting the region’s important ecosystem at risk.

Mangroves play an important role as a natural barrier that contains wind and tidal erosion, contribute to the maintenance of the coastline and the support of sand on the beaches, filter water, supply groundwater, capture greenhouse gases, act as a carbon sink, and support fish production, one of the main livelihoods in the region.

Ciudad del Carmen is a coastal city located in the Gulf of Mexico region. The population of the city grew exponentially during the 1970s due to the oil industry, developed by PEMEX (Petróleos Mexicanos). In a matter of 10 years, this fossil fuel and its exploitation attracted workers and families from all over the country, and the population grew from around 50,000 to almost 300,000, which caused serious problems when it came to creating infrastructure and services for all the people who needed accommodation in the area. At present, the oil industry is disappearing from the area because 80% of the oil reserves have been consumed and only 20% is difficult to access, for which non-traditional methods, such as fracking, have to be used.

One of the island’s problems is the sewage system, which causes continuous flooding in most of the city’s streets, leaving them completely flooded and difficult to access, and the perimeter of the island remains polluted due to the deficient water filtering system. Despite this, there are workers in the area who continue to catch shellfish or contaminated fish locally for their own use or for sale to small businesses.